New £2 million partnership to push forward research in an emerging field of science called optogenetics <em>- News</em>

See also:

Wednesday 27 January 2010

By Colin Smith

Scientists are developing a new genetic engineering technique called optogenetics that they hope could ultimately lead to a new treatment for people with the eye condition Retinitis Pigmentosa, in a £2 million funded project announced today, involving researchers from Imperial College London and European partners.

Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) is a group of hereditary eye disorders affecting approximately one person in every 3,500. In the early stages, this leads to poor night vision, leading to tunnel vision, which gradually narrows until there is a total loss of sight. RP inactivates cells in the eyes called rods, which are important for night vision. As RP progresses, these cells die and this eventually results in the loss of the remaining light sensitive cells.

Optogenetics could ultimately enable scientists to re-engineer nerve cells in the eye so that they can be switched on with light rather than electrical impulses. This would make it possible to send visual information to the brain even when all the original light sensitive cells are dysfunctional.

Over the past twenty years, scientists have investigated the use of implanted electronic chips to bring back vision. However, the complex architecture of the eye has made progress very slow. This means that scientists have only been able to achieve basic visual resolutions with their technology.

The scientists behind the new project say that their approach will enable more complex visual information to be sent to eye. This means that people with RP will get a much clearer image with better definition and contrast than is possible using implanted electronic chips.

Optogenetics

The new optogenetic technique will enable researchers to target individual cells, making different types of cells sensitive to different colours of light. The technique genetically alters nerve cells to express a protein called channelrhodopsin. This is a light sensitive ion channel which allows the cell to be activated with short pulses of light, while a complementary protein called halorhodopsin can also be used to inactivate cells.

To make this technique work in people with Retinitis Pigmentosa, the researchers would inject a specially designed virus containing channelrhodopsin into the patient’s eyes. The virus would target and convert specific nerve cells in the eye to become light sensitive. Similar techniques are already being trialled for other gene therapies.

The square dots of light are stimulating thousands of nerve cells in mouse models

Light emitting glasses

The researchers will also create special glasses that can emit light to switch the nerve cells on and off. The glasses will incorporate a miniature video camera that records information about the environment that the wearer is walking through. This information will be sent to micro-sized light emitting diodes, which will be embedded in the glasses, sending special pulses directly into the retina. The wearer’s re-engineered nerve cells will receive the encoded information, activating the cells to send the messages to the visual cortex in the brain for processing, returning vision to the wearer.

Lead researcher, Dr Patrick Degenaar, from the Institute of Biomedical Engineering at Imperial College London, says:

“This exciting project will build the basic molecular, genetic, and optoelectronic tools that we need to develop before we can start working with patients. It is very early days, and the safety of the new genetic technique will be paramount. If successful, it will return a level of vision not previously possible. I would expect optogenetic retinal prosthesis to allow patients to be able to navigate and detect the existence of key features and objects, but people will probably still need assistance for complex tasks such as face recognition and the reading of small print.”

The scientists hope that success on this project will allow them to move towards clinical trials of their new technology within the next five to ten years.

The next steps

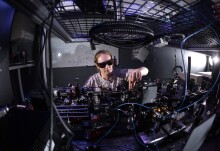

So far, the researchers have demonstrated the use of channelrhodopsin to make retinae and brain nerve cells in mouse models light sensitive. Initial prototypes of a special micro Light Emitting Diode array have also been made and shown that they can switch the cells ‘on’ and ‘off’ using tiny pin-pricks of light in the laboratory.

Research partners at the Max-Planck Institute for Biophysics and the Friederich Miescher Institute will develop new types of enhanced channelrhodopsin, and genetic methods of putting them into the eye.

At the same time, Imperial researchers and scientists from the Tyndall Institute in Ireland will develop the opto-electronic array, consisting of Light Emitting Diodes that are controlled by special electronic chips. The opto-electronic array will take visual information and encode it into special patterns of light. This will allow researchers to control thousands of nerve cells with different light colours, so that complex commands can be sent to a large number of nerve cells simultaneously.

The European Commission funded project is coordinated by Dr. Patrick Degenaar, from the Centre of Neuroscience and the Institute of Biomedical Engineering at Imperial College London. The team includes Professor Ernst Bamberg from the Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, Dr Botond Roska from the Friederich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, Professor Mark Neil from the Physics Department, Imperial College London, Brian Corbett from the Tyndall National Institute at University College Cork in Ireland and Scientifica Limited.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) available under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Creative Commons license.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.