A study of the 'spectral colour' of animal populations and their habitats shows they are linked, and that both are becoming more blue. Scientists say this has an effect on extinction rates - News

Thursday 7 April 2011

Adapted from a news release by British Ecological Society

The 'colour' of our environment is becoming 'bluer', a change that could have important implications for animals' risk of becoming extinct, say ecologists from Imperial College London this week.

See also:

Related news stories:

In a major study published this week in the British Ecological Society's Journal of Animal Ecology, researchers examined how quickly or slowly animal populations and their environment fluctuate over time, something ecologists describe using 'spectral colour'.

Previous studies show that the spectral colour of a population is linked to its risk of becoming extinct; now this study shows a way that climate change could impact the extinction risk of populations by affecting the colour of populations.

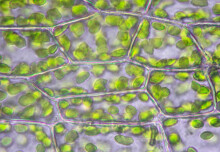

Ecologists have investigated the link between fluctuations in the environment and those of animal populations for the past 30 years. They describe fluctuations as a colour spectrum, where red signifies an environment or population that fluctuates more slowly over time (such as ocean temperature) and blue signifies more rapid fluctuations (such as changes in air temperature).

Existing models and theories suggest that the spectral colour of the environment should affect the spectral colour of animal populations. Now for the first time ecologists have assembled field data to help confirm the theory.

They showed that the colour of changes in the environment does map onto the colour of changes in animal populations, meaning there are redder (slower) fluctuations in population size if there are also redder (slower) fluctuations in aspects of the environment. Furthermore, they found that our environment is becoming 'bluer', in other words fluctuating more rapidly over time.

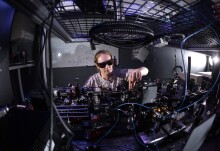

Bernardo Garcia-Carreras and Dr Daniel Reuman examined three large sets of data. They used the Global Population Dynamics Database, from which they extracted data on changes in population for 147 species of bird, mammal, insect, fish and crustacean over the past 30 years, and two sets of temperature data from the Climatic Research Unit and the Global Historical Climatology Network. The latter includes data collected from weather stations worldwide throughout the twentieth century.

Mr Garcia-Carreras, who is a Natural Environment Research Council-funded PhD student in Imperial's Department of Life Sciences, explained: "The colour change refers to the change in 'spectral colour' but this does not mean that red means warmer temperatures. Spectral colour tells us how quickly or slowly temperature is oscillating over time. If the oscillations are comparatively slow, then we say that temperature has a 'red' spectrum, and if the changes are quick, then temperature is said to be 'blue'. When we talk of temperature becoming 'bluer', we mean the oscillations in temperature are becoming faster over time."

While the study seems to provide some good news for species facing extinction, the researchers warn that this is offset by other pressures. Dr Reuman, also from Imperial's Department of Life Sciences, said: "This apparent good news is tempered by the fact that habitat loss, overexploitation and other factors are likely more important drivers of extinction risk than the colour of temperature fluctuations."

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) available under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Creative Commons license.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.