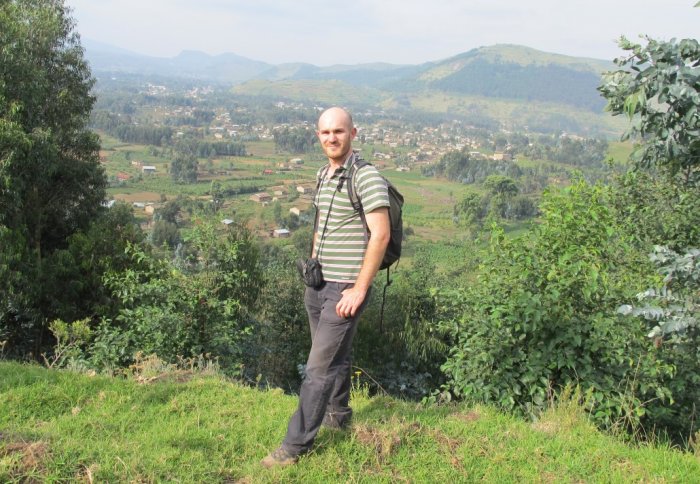

Postgraduate student Leo Peskett, Basu Civil Engineering Prize winner, talks about his summer field trip to Rwanda to investigate geothermal energy.

For most people, Rwanda is still synonymous with the terrible genocide that afflicted the country 20 years ago - as well as the period of reconciliation and economic recovery that followed. Rwanda is now relatively stable politically, has good roads, a high standard of education and excellent healthcare. But being a densely populated, landlocked country with no fossil fuel and limited hydroelectric power, energy security is a big issue.

Leo Peskett, who is currently studying for an MSc in Engineering Geology at Imperial, first visited Rwanda in 2012. He was there working with government officials on environmental policy , a line of work he first began as a Research Fellow at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) - an independent think tank based in London. Whilst in Rwanda he also became aware of the potential of geothermal energy in the country’s Virunga Mountains, which is actually a series of dormant volcanoes sitting on the edge of Africa’s Great Rift Valley, where two tectonic plates are slowly being pulled apart. This type of geothermal energy basically involves drilling deep into volcanically active regions with the aim of finding groundwater at high temperatures and pressures that can be used to produce steam to drive turbines.

Leo Peskett, who is currently studying for an MSc in Engineering Geology at Imperial, first visited Rwanda in 2012. He was there working with government officials on environmental policy , a line of work he first began as a Research Fellow at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) - an independent think tank based in London. Whilst in Rwanda he also became aware of the potential of geothermal energy in the country’s Virunga Mountains, which is actually a series of dormant volcanoes sitting on the edge of Africa’s Great Rift Valley, where two tectonic plates are slowly being pulled apart. This type of geothermal energy basically involves drilling deep into volcanically active regions with the aim of finding groundwater at high temperatures and pressures that can be used to produce steam to drive turbines.

Seeing that potential and what it could mean for the country sparked the first rumblings of a change in direction for Leo - from largely desk-based policy work to field geology.

“I’ve spent nine years working on international environmental policy; I’ve had the chance to work on many interesting international projects linked to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. But it is ultimately a world of negotiations, meetings and words, and I’ve been yearning to complement it with some more technical, scientific and field based work. I wanted to be more connected with projects - more hands on.”

The Virunga range. From left to right, Muhabura, Gahinga, Karisimbi, Sabyinyo, Mikeno

For this to happen, Leo needed specialist training and Imperial seemed the obvious choice with his being based in London and the excellent postgraduate offerings in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. It was partway through his ‘intense’ course that Leo heard of the annual Basu Prize for Civil Engineering - a competition that funds the best proposal for an overseas MSc dissertation project (see panel, right).

For Rwanda, energy independence is perhaps the government’s biggest challenge

– Leo Peskett

MSc in Engineering Geology

Still incubating that seed of an idea to return to Rwanda and further explore the potential of geothermal energy, Leo saw the Basu prize as a way to realise that dream and also complete his dissertation in a fascinating part of the process just after the country had drilled two exploratory boreholes. Luckily for him, he was successful and he flew out to the capital Kigali on 15 June for three weeks.

“For Rwanda, energy independence is perhaps the government’s biggest challenge. They’re currently relying on limited hydropower and massive generators on the outskirts of the major cities which run on expensive fuel, driven in from over the border. It’s not economically or environmentally sustainable. What’s more they can’t develop big industry or give electricity access to their citizens without a cheaper, more readily available solution.”

Leo already had a reasonable knowledge of the context of geothermal energy in Rwanda: research into its potential originally began in 2006 and over the following six years a series of major surveys were carried out across the Virunga range. This survey work consisted of geophysical, geochemical and geological investigations and has helped to define a ‘conceptual model’ of what might actually be under those mountains. Based on this work, exploratory drilling began on the promising Mount Karisimbi inactive volcano in July 2013. Two boreholes were drilled to depths of up to 3km, but unfortunately, for as yet unknown reasons, no suitably hot geothermal resource was found.

Leo already had a reasonable knowledge of the context of geothermal energy in Rwanda: research into its potential originally began in 2006 and over the following six years a series of major surveys were carried out across the Virunga range. This survey work consisted of geophysical, geochemical and geological investigations and has helped to define a ‘conceptual model’ of what might actually be under those mountains. Based on this work, exploratory drilling began on the promising Mount Karisimbi inactive volcano in July 2013. Two boreholes were drilled to depths of up to 3km, but unfortunately, for as yet unknown reasons, no suitably hot geothermal resource was found.

“They have to get 2600m up the side of the volcano with all the equipment and then drill back down a depth of 3000m. The first 1000m or so is mostly lava, which contains some large cavities that make drilling very problematic and that’s before you get to the granites, which contain geothermal waters in fracture networks, provided they’re even there of course. It’s really not easy to find the right spot to drill from a scientific and engineering point of view,” Leo says.

The international community is providing funding for additional exploratory boreholes, but there is a need to better hone the geological model of the area to increase the likelihood of success. And that’s where Leo saw an opportunity to make a contribution.

His first job out in Rwanda was to access recent survey data that was not available online and stored in the capital Kigali, particularly on the recent drilling programme. Given that he still had some government contacts in Kigali from his previous work there, Leo was able to obtain and analyse these records.

His first job out in Rwanda was to access recent survey data that was not available online and stored in the capital Kigali, particularly on the recent drilling programme. Given that he still had some government contacts in Kigali from his previous work there, Leo was able to obtain and analyse these records.

He also was able to get out into the field in the Virunga mountains and do some field-based structural geology and real world observation.

“That’s what we’ve been training at Imperial to do. There are lots of signs you can look for in the different types of surface rocks, particularly large faults and smaller fractures in the rock. How frequently the fractures occur, what orientation they are in and the aperture of the fracture. That gives you an idea of permeability of the underlying rock, which is essential for geothermal energy as it means the rock below could be holding and circulating water. It’s basic stuff, but it’s really important.”

With this work Leo has built a more detailed geological model of the area focussed on groundwater flow, drawing on all of the existing literature and the new work. He hopes others might continue using similar methods to help inform future drilling operations.

“There was of course a limit to what I could do in the three weeks I was there, but I hope to recommend things that may be of help to the Government of Rwanda .

“I’d love to have come back and said, it’s all great, they’ve got a definite resource and they’ll be generating energy very soon. But that’s not how geology and engineering projects like this work; it requires patience and careful, comprehensive assessment. But the government is definitely getting closer.”

For Leo now, it’s off to do a PhD in a related area of hydrogeology at the University of Edinburgh - furthering his skill set in geological engineering now he’s caught the fieldwork bug. But he definitely doesn’t discount looking into the Rwanda project again at a later date.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) available under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Creative Commons license.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Andrew Czyzewski

Communications Division

Contact details

Email: press.office@imperial.ac.uk

Show all stories by this author

Leave a comment

Your comment may be published, displaying your name as you provide it, unless you request otherwise. Your contact details will never be published.