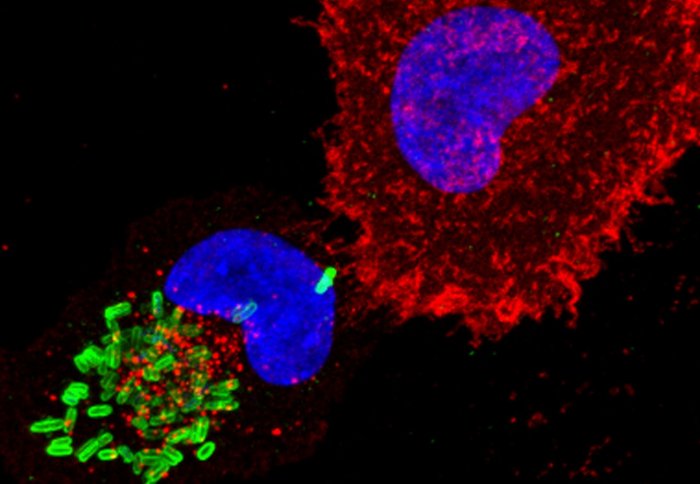

Salmonella (green) infect a human cell

Scientists have discovered that Salmonella causes disease by preventing deployment of the immune system's 'SAS'.

When harmful bacteria invade our body, the immune system releases an elite force of cells to destroy the invader. Salmonella are sometimes able to overcome these ‘SAS’ cells – called T-cells – but until now, scientists didn’t know how.

However, new research, from scientists at Imperial College London, shows that Salmonella use a sophisticated trick to disable this key line of defence against them.

The team behind the new research say the findings may help improve the effectiveness of vaccine against Salmonella, and even other bacteria and viruses.

Video caption: Salmonella bacteria infecting human cells

How salmonella works

Salmonella is one of the leading causes of food poisoning across the world. The bacteria are also responsible for typhoid fever, which affects around 20 million people each year.

When disease-causing bacteria infect our bodies they are met with two lines of defence. The first, called the innate immune system, acts immediately, ready to fight many invaders.

The second line - called the adaptive immune system – takes several days to develop, but then deploys elite ‘special forces’ against the invading bacteria – called T cells. These ‘SAS’ cells efficiently kill the bacteria and keep a memory of the invader, so that it’s instantly recognised next time it attacks.

The second line - called the adaptive immune system – takes several days to develop, but then deploys elite ‘special forces’ against the invading bacteria – called T cells. These ‘SAS’ cells efficiently kill the bacteria and keep a memory of the invader, so that it’s instantly recognised next time it attacks.

The adaptive immune system is usually triggered when an immune cell 'eats' an invading bacterial cell. Fragments of digested bacteria are then displayed on the outside of the immune cell. The SAS cells see these bits of bacteria on the outside of the cell, and are triggered to mount an attack.

Evading attack

Research from the Imperial team, published in the journal Cell Host and Microbe, shows that Salmonella prevents the immune cells from displaying digested bacterial fragments on their surface.

The bacterial cell is 'eaten' as normal, but the Imperial team found that once inside the cell, the bacteria release a specific protein that disrupts the transport of bacterial fragments to the cell surface. This prevents the immune system's second wave of defence – the SAS cells - being activated.

The scientists also found that the Salmonella protein works ingeniously - by hijacking machinery inside the immune cell and forcing it to destroy the fragments of bacteria, rather than taking them to the cell surface.

This is a very small protein but it packs a big punch

– Professor David Holden

Director of the MRC Centre for Molecular Bacteriology and Infection

Professor David Holden, senior author of the study and Director of the MRC Centre for Molecular Bacteriology and Infection at Imperial said: "This is a very small protein but it packs a big punch – accounting in part for the ability of Salmonella to cause infections. Now we have this knowledge, we might be able to use it to enhance the effectiveness of vaccines against Salmonella and possibly other harmful bacteria and viruses."

–

"The Salmonella Effector SteD Mediates MARCH8-Dependent Ubiquitination of MHC II Molecules and Inhibits T Cell Activation" by E. Bayer-Santos et al is published in Cell Host & Microbe.

The research was funded by the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust.

Supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) available under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Creative Commons license.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Kate Wighton

Communications Division

Contact details

Email: press.office@imperial.ac.uk

Show all stories by this author