Tracing the evolution of Imperial College London from the nineteenth century to the present day.

Earlier this month the Imperial Festival attracted 15,000 guests to the South Kensington Campus in an extravaganza of science and art exhibited by talented and creative people of many different nationalities.

Impressive as the festival has become in its fourth outing, its scale is far from unprecedented in local history and indeed Imperial has its very roots in a similar but far larger event that happened one hundred and sixty four years ago last month.

In May 1851 Hyde Park hosted The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations (or ‘The Great Exhibition’) – the first event of its kind in the world, housed in a monumental glass house filled with over 100,000 exhibits.

In May 1851 Hyde Park hosted The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations (or ‘The Great Exhibition’) – the first event of its kind in the world, housed in a monumental glass house filled with over 100,000 exhibits.

It was the first step in the vision of Prince Albert, who wanted to “increase the means of industrial education and extend the influence of science and art”. Such a grand ambition had required the creation of a Royal Commission to oversee its mission (see right panel).

Early beginnings

The Great Exhibition turned out to be a great success, attracting six million visitors between 1 May and 11 Oct 1851 and even turning a tidy profit of £186,000 thanks to an entrance fee of around 5 shillings plus a supplementary fee of a penny to use the flush toilets (a novelty back then).

That enabled the Royal Commission to continue Albert’s vision through the acquisition of an 87 acre plot of land in South Kensington.

The main square took form in 1855 when the roads of Kensington Gore, Exhibition Road, Cromwell Road and Queen’s Gate were laid out and work began on the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) and the Central Hall of Arts and Science (later renamed the Royal Albert Hall).

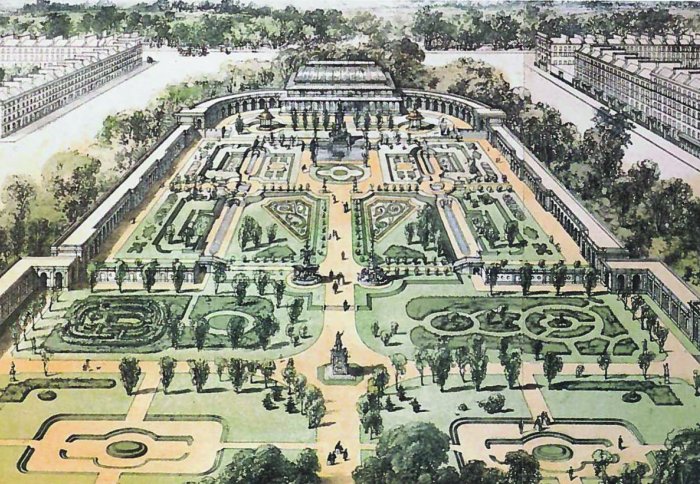

Within this square, where Imperial now resides, a stunning garden was landscaped by the Horticultural Society, which in 1870 was enclosed on each side by the ‘Eastern and Western Galleries’ – continuing the spirit of the Great Exhibition with ‘miscellaneous displays of science and art’.

All that remains on Campus from these formative early years is a section of the Western Gallery wall at the back of the Sherfield Building, draped in ivy looking every bit a vestige from a different era. Last month a commemorative plaque was installed on the wall by the 1851 Commission to inform visitors and passers-by what once was.

Education

Central to Prince Albert’s vision was to create a great educational centre, and in 1872 the Royal School of Mines was persuaded to move onto the estate, where the Royal College of Science was later created.

The two Colleges were incorporated by Royal Charter into The Imperial College of Science and Technology in 1907, while The City and Guilds College was incorporated in 1910.

One of the most notable academics from the early days of the constituent Colleges was biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, dubbed ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ for his staunch advocacy of evolution. Meanwhile, one of the most famous students at the time was H.G Wells (left), who was taught by Huxley but failed his final exams and went on to become a famous science fiction author.

One of the most notable academics from the early days of the constituent Colleges was biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, dubbed ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ for his staunch advocacy of evolution. Meanwhile, one of the most famous students at the time was H.G Wells (left), who was taught by Huxley but failed his final exams and went on to become a famous science fiction author.

The end of the 19th Century ushered in an era of frenzied building activity on the estate, involving some of the great architects and engineers of the day, including Alfred Waterhouse who designed the Natural History Museum (1880) and the now demolished City and Guilds Building (1881) and Sir Aston Webb who designed the Royal School of Mines building (1907) and the now demolished Royal College of Science building (1906).

The centrepiece of the estate though was T.E. Collcutt’s Imperial Institute, completed in 1893 with its three iconic Renaissance-style towers.

Renewal

The first five decades of the 20th Century would see Imperial cement its reputation as a leader in science and engineering, playing host to pioneering work in radioactivity and particle physics, zoology, aeronautics and engineering under notable names such as Robert Strutt (4th Baron Rayleigh), W.E. Dalby and Sir Alec Skempton.

In the late 1950s the government’s policy to expand UK science and Imperial’s own need for modern laboratories ultimately led to the demolition of nearly all the Victorian-era buildings. Only a vociferous campaign saved the Central Tower, which became known as the Queen’s Tower.

In the late 1950s the government’s policy to expand UK science and Imperial’s own need for modern laboratories ultimately led to the demolition of nearly all the Victorian-era buildings. Only a vociferous campaign saved the Central Tower, which became known as the Queen’s Tower.

By the 1960s, the expansion of the modern era college was well underway, with the Blackett Laboratory, Aeronautics and Chemical Engineering (ACE) Building and the foundations of the Sherfield Building all in place.

Aside from additions such as the Main Entrance and Faculty Building, the same basic site plan remains today, whilst the Royal Commission, from its base in the Sherfield Building, continues to be Imperial’s ground landlord charging a modest rent on a 999 year lease.

Sherfield foundations and 1870 arches

Compiled with assistance from Anne Barrett (Archivist & Corporate Records Manager at Imperial) and Angela Kenny (Archivist & Alumni Relations at the Royal Commission for 1851).

Find out more about Imperial's history here: //www.imperial.ac.uk/about/history/

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) available under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Creative Commons license.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Andrew Czyzewski

Communications Division

Contact details

Email: press.office@imperial.ac.uk

Show all stories by this author

Leave a comment

Your comment may be published, displaying your name as you provide it, unless you request otherwise. Your contact details will never be published.

Comments

Comments are loading...