Research suggests human to human transmission of H5 influenza viruses is unlikely - <em>News Release</em>

Imperial College London News Release

Under STRICT embargo until:

17.00 PST, Wednesday 18 November

(01.00 GMT, Thursday 19 November)

Bird flu viruses would have to make at least two simultaneous genetic mutations before they could be transmitted readily from human to human, according to research published today in PLoS ONE.

See also:

Related news stories:

The authors of the new study, from Imperial College London, the University of Reading and the University of North Carolina, USA, argue that it is very unlikely that two genetic mutations would occur at the same time. Today's new study adds to our understanding of why avian influenza has not yet caused a pandemic.

Earlier this year, the Imperial researchers also showed that avian influenza viruses do not thrive in humans because, at 32 degrees Celsius, the temperature inside a person's nose is too low.

H5 strains of influenza are widespread in bird populations around the world. The viruses occasionally infect humans and the H5N1 strain has infected more than 400 people since 2003.

H5N1 has a high mortality rate in humans, at around 60 per cent, but to date there has been no sustained human to human transmission of the virus, which would need to happen in order for a pandemic to occur.

Today's study suggests that one reason why H5N1 has not yet caused a pandemic is that two genetic mutations would need to happen to the virus at the same time in order to enable it to infect the right cells and become transmissible. At present, H5 viruses can only infect one of the two main types of cell in the mouth and nose, a type of cell known as a ciliated cell. In order for H5 to transmit from human to human, it would need to be able to infect the other, non-ciliated type of cell as well.

To infect a cell, the influenza virus uses a protein called HA to attach itself to a receptor molecule on the cell's surface. However, it can only do this if the HA protein fits that particular receptor. Today's research shows that H5 would only be able to make this kind of adaptation and fit the receptor on the cells that are important for virus transmission if it went through two simultaneous genetic mutations.

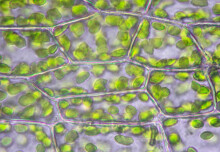

H5 influenza viruses are endemic in bird populations around the world

Professor Wendy Barclay, corresponding author of the study from the Division of Investigative Science at Imperial College London, said: "H5N1 is a particularly nasty virus, so when humans started to get infected with bird flu, people started to panic. An H5N1 pandemic would be devastating for global health. Thankfully, we haven't yet had a major outbreak, and this has led some people to ask, what happened to bird flu? We wanted to know why the virus hasn't been able to jump from human to human easily.

"Our new research suggests that it is less likely than we thought that H5N1 will cause a pandemic, because it's far harder for it to infect the right cells. The odds of it undergoing the kind of double mutation that would be needed are extremely low. However, viruses mutate all the time, so we shouldn't be complacent. Our new findings do not mean that this kind of pandemic could never happen. It's important that scientists keep working on vaccines so that people can be protected if such an event occurs," added Professor Barclay.

Professor Ian Jones, leader of the collaborating group at the University of Reading, added: "It would have been impossible to do this research using mutation of the real H5N1 virus as we could have been creating the very strain we fear. However, our novel recombinant approach has allowed us to safely address the question of H5 adaptation and provide the answer that it is very unlikely."

In addition to explaining why bird flu's ability to transmit between humans is limited, the new research also gives scientists a better understanding of the virus. They believe that this could help the development of a better vaccine against bird flu, in the unlikely event that one was needed in the future.

The researchers used a realistic model of the inside of a human airway to study H5 binding to human cells. They made genetic changes to the H5 HA protein to change its shape, to see if they could make the virus recognise and infect the right types of cells. Results showed that the virus would need two genetic changes occurring at once in its genome before it could infect these cells.

The researchers then investigated intermediate forms of the virus, with one or the other mutation, to see if the change could occur gradually. They found that intermediate versions of the virus could not infect human cells, so would die out before they could be transmitted. The researchers say this means the two genetic mutations would need to occur simultaneously.

-Ends-

For further information please contact:

Lucy Goodchild

Press Officer

Imperial College London

E-mail: lucy.goodchild@imperial.ac.uk

Telephone: +44 (0)20 7594 6702 or ext. 46702

Out of hours duty press officer: +44 (0)7803 886 248

Notes to Editors:

1. "Mutations in H5N1 Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin that Confer Binding to Human Tracheal Airway Epithelium" PLoS ONE, Wednesday 18 November 2009.

Corresponding author: Professor Wendy Barclay, Imperial College London (For a full list of authors, please see paper)

2. About Imperial College London

Consistently rated amongst the world's best universities, Imperial College London is a science-based institution with a reputation for excellence in teaching and research that attracts 14,000 students and 6,000 staff of the highest international quality.

Innovative research at the College explores the interface between science, medicine, engineering and business, delivering practical solutions that improve quality of life and the environment - underpinned by a dynamic enterprise culture.

Since its foundation in 1907, Imperial's contributions to society have included the discovery of penicillin, the development of holography and the foundations of fibre optics. This commitment to the application of research for the benefit of all continues today, with current focuses including interdisciplinary collaborations to improve health in the UK and globally, tackle climate change and develop clean and sustainable sources of energy.

Website: www.imperial.ac.uk

3. The University of Reading is rated as one of the top 200 universities in the world (THE-QS World Rankings 2009), and one of the UK's top research-intensive universities. The University is ranked in the top 20 UK higher education institutions in securing research council grants worth nearly £10 million from EPSRC, ESRC, MRC, NERC, AHRC and BBSRC. In the RAE 2008, over 87% of the university's research was deemed to be of international standing. Areas of particular research strength recognised include meteorology and climate change, typography and graphic design, archaeology, philosophy, food biosciences, construction management, real estate and planning, as well as law.

University of Reading is a member of the 1994 Group of 19 leading research-intensive universities. The Group was established in 1994 to promote excellence in university research and teaching. Each member undertakes diverse and high-quality research, while ensuring excellent levels of teaching and student experience. www.1994group.ac.uk

More information at www.reading.ac.uk

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) available under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Creative Commons license.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.