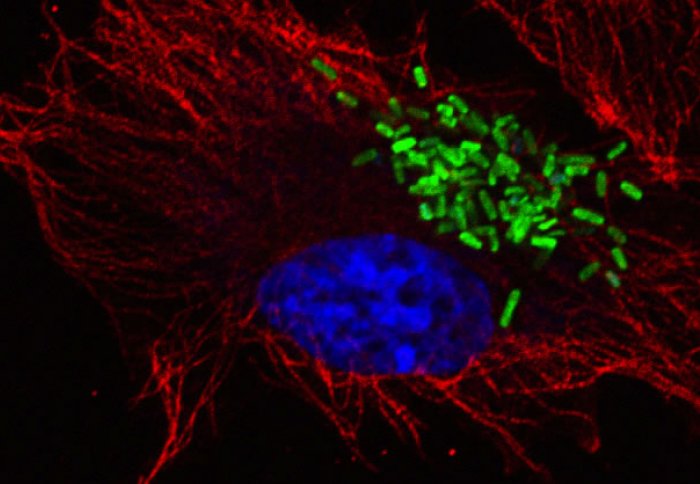

Salmonella bacteria (green) invade a red blood cell

Research led by Professor David Holden shows how Salmonella bacteria inactivate immune defences in human cells.

A new study by researchers at Imperial College London has identified a way in which Salmonella bacteria, which cause gastroenteritis and typhoid fever, counteract the defence mechanisms of human cells.

One way in which our cells fight off infections is by engulfing the smaller bacterial cells and then attacking them with toxic enzymes contained in small packets called lysosomes.

Published in Science, the study has shown that Salmonella protects itself from this attack by depleting the supply of toxic enzymes.

Lysosomes constantly need to be replenished with fresh enzymes that are generated from a factory within our cells. These enzymes are carried from the factory along a dedicated transport pathway. After dropping off new enzymes at lysosomes, the transport carriers are sent back to the factory to pick up new enzymes.

In the study, led by Professor David Holden from the Department of Medicine and MRC Centre for Molecular Bacteriology and Infection, the group discovered that Salmonella has developed a specific way to interfere with the system that restocks the lysosomes with enzymes. They found that after bacteria have been engulfed by the cell, but before they are killed, Salmonella injects a protein that prevents the cell from recycling the transport carriers between the factory and the lysosome.

This means that Salmonella effectively cuts off the supply line of the enzymes that would otherwise kill it. As a result, the enzymes get re-routed out of the cell and the lysosomes lose their potency. Salmonella is then able to exploit the disarmed lysosomes by feeding off the nutrients they contain.

Professor Holden said: “This seems to be a very effective way for these harmful bacteria to interfere with our cell’s defence mechanisms, and then exploit the defective lysosomes to their own benefit.”

“Our challenge now is to understand in greater detail how the injected Salmonella protein works at the molecular level, and – potentially – to exploit our findings to develop more effective vaccines. This is especially important since many Salmonella strains are now resistant to antibiotics.”

Different strains of Salmonella cause gastroenteritis, blood infections and typhoid fever, which together are responsible for millions of human illnesses and deaths each year.

The research project was funded with grants from the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust.

Supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) available under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Creative Commons license.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Mike Jones

Enterprise

Contact details

Tel: +44 (0)20 7594 3891

Email: michael.jones1@imperial.ac.uk

Show all stories by this author

Leave a comment

Your comment may be published, displaying your name as you provide it, unless you request otherwise. Your contact details will never be published.